by Greg Ritchie

A Caribbean island’s suspended debt payments may offer a template for other nations hit by disasters, as the risks from climate change grow.

Grenada is acting as a test case, with officials set to meet bondholders on Friday to discuss its first use of a so-called hurricane clause. That’s enabled it to avoid making bond payments for the coming year in the wake of Hurricane Beryl in July. The clause was introduced in 2015 following a default, as the country struggled to recover from a series of devastating storms.

The concept has so far failed to gain much traction in the bond market, though it’s starting to appear in institutional loans, and some investors are now calling for wider adoption. Grenada’s bonds look largely unperturbed by the decision to defer payments, which may help convince skeptics that such provisions won’t jeopardize creditor returns.

“There should be more bonds like this. For me, these are good instruments,” said Luc D’Hooge, a fund manager at Vontobel Asset Management, which owns some of the Grenadian debt. “It’s not that costly for bondholders either, but clearly a near-term cash relief for Grenada.”

The effort to address disaster risk comes as investors are assessing how climate change will impact government debt and sovereign ratings in future, with an S&P Global Ratings analysis seeing poorer countries such as small island states four times as exposed as richer peers. As the planet warms, modeling firm Verisk estimates natural disasters may cause insurance losses to surge 40% to around $150 billion a year.

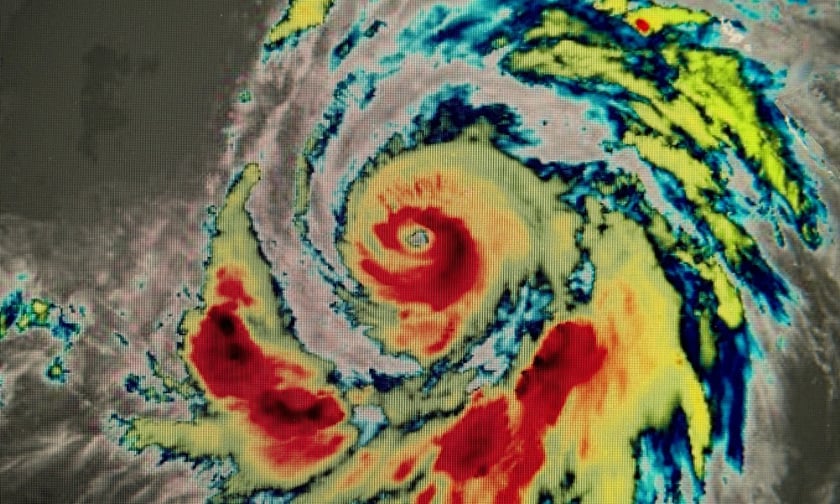

Hurricanes are among the most destructive events, with Jamaica having recently taken out a catastrophe bond — a separate instrument akin to an insurance policy — against such risks. Beryl damaged nearly every building on Grenada’s Carriacou island, and the government estimated total losses equate to about a third of its annual gross domestic product.

“The damage is significant,” said Mike Sylvester, permanent secretary at the nation’s ministry of finance, citing the need for debris removal after Beryl as well as repairing buildings and agriculture.

“The hurricane clause will allow the government the ability to respond adequately and decisively to the disaster.”

While still a novelty in bonds, similar clauses are appearing in loans from official institutions. In 2022, UK Export Finance — Britain’s export credit agency — started providing low-income countries and small island states the ability to defer debt repayments in the event of a severe climate shock or natural disaster. The World Bank now also offers two-year disaster pauses on some of its loans.

“If every developing country had these clauses in their debt, it would transform the global financial system from one that amplifies shocks in developing countries to one that absorbs them,” said Avinash Persaud, special adviser on climate change at the Inter-American Development Bank, which also uses such clauses in loans. “No other instruments provide this scale of liquidity as quickly and cheaply as these clauses.”

Grenada’s clause only defers coupon and principal payments. Its total debt servicing costs over the course of the bond will increase in nominal terms because the deferred interest is added to the principal, creating larger future interest payments. That’s why the bonds haven’t taken a hit, said Samy Muaddi, head of emerging-markets fixed income at T. Rowe Price.

The nation has also embedded hurricane clauses into its bilateral loans, which may ease cash obligations as it focuses on its recovery. The country was battered by Hurricane Ivan in 2014, which began a decade of economic malaise that resulted in its default. It’s now running budget surpluses, helped in part by revenue from its citizenship-by-investment or “golden passport” program.

While global policy momentum is firmly behind debt sustainability, it may still prove challenging to change market practice. Barbados’ insertion of a hurricane clause into its bonds — the only other country to have followed Grenada’s example — required much wrangling with skeptical creditors.

In the end, it was only accepted after making a concession to bondholders. If natural disaster strikes, Barbados has to notify creditors of its intent to enact the clause. If a committee majority votes against its use, it can’t be enacted.

In Grenada’s case, investors seem understanding. T. Rowe Price holds the debt, having been a long term investor in the country, with Muaddi saying the move to defer payments was no surprise.

“The form of the clause is helpful for the country,” he said. “It’s architecturally significant to the market in terms of how climate resilient debt clauses can be implemented and practiced.”

Copyright Bloomberg News